In my previous blog post covering SQL, we covered its foundations: how to retrieve specific data, join tables together, and aggregate rows to find trends. These commands (SELECT, FROM, JOIN, GROUP BY) are the bread and butter of data analysis in SQL.

But what happens when your question gets more complicated?

Imagine you need to answer this: "Who are the employees earning more than the average salary of the entire company?"

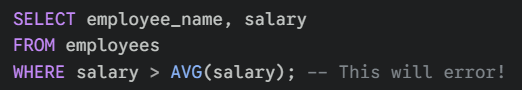

Your first instinct may be to write this:

This query fails because of the Order of Operations of SQL (again, see my last blog post). The database cannot filter (WHERE) based on an aggregation (AVG) that hasn't happened yet.

To solve this, we need to calculate the average first, and then pass that number into our filter. We need to perform a query inside a query. This brings us to the next level of SQL mastery: Subqueries and Common Table Expressions (CTEs).

Subqueries

A subquery is exactly what it sounds like: a query nested inside another query. It allows you to run a separate calculation and pass the result to your main query dynamically.

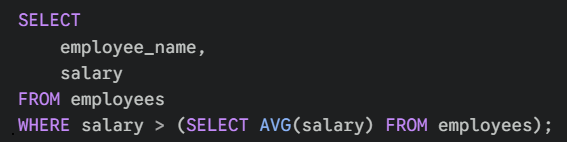

To answer our question about salaries, we can use a subquery in the WHERE clause:

How it works: The database runs the inner query (in the parentheses) first. It calculates the average (e.g., 50,000). Then, it runs the outer query, effectively treating it as: WHERE salary > 50000.

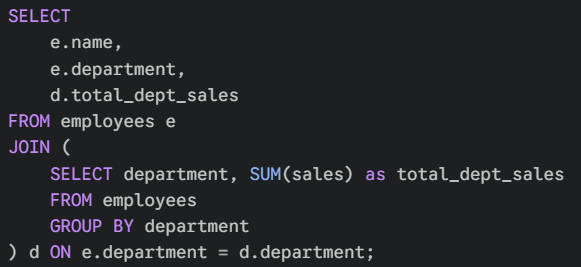

Subqueries in the FROM clause: You can also use subqueries to create a temporary "table" to query from. This is useful if you want to aggregate data and then join it back to the original table.

For example, if you wanted to see every employee alongside the total sales of their specific department:

While this solution works, the limits of subquerying becomes clear. They force you to read code from the inside out. As your analysis gets more complex, your code becomes a mess of nested parentheses, making it difficult to spot errors or understand the logic at a glance.

Enter CTEs (Common Table Expressions)

Think of a CTE as "showing your working" in a math problem. Instead of trying to solve the whole equation in one go (as in a subquery), you calculate the intermediate steps first, give them clear names, and then use those results to find your final answer.

A CTE creates a temporary result set that exists only for the duration of the query. They simplify complex queries, make them easier to read, and can be reused multiple times within the same query.

They are defined using the WITH keyword at the very top of your script.

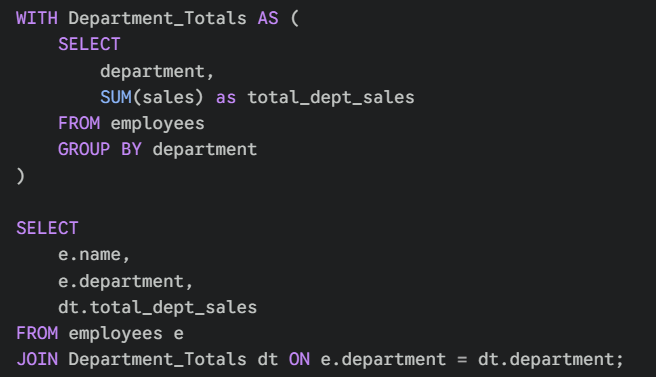

Here's the previous "Department Sales" example using a CTE this time:

Why is this better?

- Readability: You give the complex logic a name (

Department_Totals). Anyone reading the code knows exactly what that table represents before they even reach the finalSELECT. - Reusability: You can reference

Department_Totalsmultiple times in your main query without having to rewrite the subquery logic every time.

So when should I use which?

Now that you have both tools in your arsenal, you might wonder when to use which.

While subqueries are excellent for quick, one-off filters (like the first example finding salaries above average), CTEs are the industry standard for complex analysis.

In the consulting world, code is rarely written for just one person. It is shared, reviewed, and debugged by teams. Because CTEs read from top-to-bottom rather than inside-out, they are much easier for your colleagues (and your future self) to understand.

If your query requires more than one step of logic, or if you find yourself nesting parentheses inside parentheses, stop and rewrite it as a CTE. Your team will thank you!

Conclusion

Subqueries and CTEs help bridge the gap between simple data retrieval and more sophisticated data analysis. They allow you to answer complex, multi-layered questions directly within your query.

The key to mastering them is remembering that code is meant to be read. While subqueries are useful tools for quick fixes, building the habit of using CTEs will make your work cleaner, more logical, and scalable.

Start simple, break your problems down into steps, and you will be writing advanced SQL in no time.

-- Tyler